The first thing I noticed while driving down the streets of Edinburgh was its cohesion. Like the rock walls that followed the road, each house was placed carefully to match those surrounding it, the end result – a unified line of design. Coming from a newly formed colonial state I realized that a key outcome of colonialism is disruption. Of culture, people , place, even architecture. It is an inherently destabilizing force that shakes the very foundations of a country, making cohesion practically impossible. colonization is a disruptor. However, this does not mean that Edinburgh has never been touched by the gloved hand of English empire building. In many ways the effects of cultural domination can be most acutely felt in the places closest to the castle. Here invasion is dressed up as a gaudy colored imperial band marching down the street to god save the queen. While bayonets are replace by baritones, the effects can be the same.

I was taught how to travel by my grandparents. This has resulted in what some people would call slightly old-fashioned way of moving through places. The first thing I do in a new city is get a physical map that I can hold in my hands and then stuff into the bottom of my bag and eventually forget about. A good map provides a guide, not only for finding things but for getting lost, not only in a cities’ scenery but its history. The map of Edinburgh is essentially divided into two parts – ‘old town’ and ‘new town’. These simplistic labels hide a very complicated relationship between Scotland and Edinburgh.

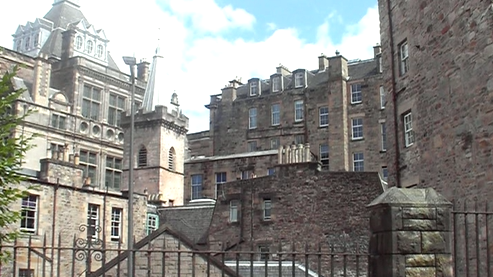

Edinburgh is a city defined by walls, you can’t escape them as you wonder around the gates of fortified castle. A castle that has been under siege more then 20 times, making it one of the most besieged defenses in Europe. The walls weren’t just decoration but provided protection from the growing reach of the English empire. As the threat of invasion continued to rise and the population swelled the only option was to build upwards. In the seventeenth century, Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe said “that in no city in the world [do] so many people live in so little room as Edinburgh”. Teetering stacks of rooms built on top of one another, looking over a labyrinth of alleyways that eventually disappear under bridges, over hills and around corners. In this disordered cityscape poverty triumphed over prosperity. The voracious expansion of oldtown within the confines of Edinburgh’s walls caused a slumifaction of the city, condemning its inhabitants to a life of disease and misfortune, besides the elite few who lived in the top floors, positioned as far as possible from the decay that had taken over the alleyways.

While class-based discrimination was rife in oldtown the wealthy and the poor were forced to live in close proximity. This antagonistic existence continued until the ‘act of union’ that formally announced the end of Scottish independence and its submergence into the ‘greater’ English empire. As the parliament and power left Edinburgh so did most of its prosperous class leaving behind a city that was still struggling to rise above the confines of its fortified walls. Nearly 50 years after the ‘great’ union a solution was finally proposed. Old town was becoming a failed city, development could not keep pace with the declining standards of living. The answer was to build a new town. And in this town house a certain type of people, a type of people that had not been touched by the dirty hands of poverty,This was to be a town for the new aristocracy, it was designed to house the wealthy and attract the prosperous class back. Old town would remain the same – ridden with disease and suffocating from overcrowding, falling into itself because of deteriorating infrastructure.

In 1767 a competition was held for the design of Edinburgh’s new town. Inspired by the Georgian style of the time, the houses in new town were spaciously built. Symmetrical, uniform and planned, everything that old town was not. This estate for the elite was made with wide avenues that sweet around open parks. Parks that to this day are guarded under lock and key in case any of the city’s peasantry decided they want to feel like the gentltry for a day. Overall the solution was a ‘success’, the rich returned. New town was built with street names that reflect England increasing disruption of Scottish culture. George street, queen’s street, princess street. A town organized by , and for, the new ruling class.

I was walking around oldtown one day using my map to try and find the most exciting route to work and I stumbled upon a staircase. ‘Jacob’s ladder’ a steep winding flight of steps that connects the old with the new. A name that come from the bible, Genesis 28, where Jacobs falls asleep.

And he dreamed, and behold, there was a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven. And behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it! And behold, the Lord stood above it and said, “I am the Lord, the God of Abraham”

Originally used as a procession route for funerals, Jacob’s ladder became one of the only thoroughfares for people from oldtown to access the newly built town above. 140 stone steps carved into volcanic rock marked their ascent from a world stained by poverty to one shinning in wealth. I wonder if they also thought that at the top they would find heaven? . Walking up this staircase you realise that the top is much narrow then the bottom causing those coming from ‘bellow’ (from earth, old town) to physically move out of the way of those descending from the top (heaven, new town). In a symbolic way the people who would use Jacob’s ladder were all angels. Minimum wage workers from old town who had been hired to serve the needs of the new aristocracy.

I released that architecture both reflects and reaffirms class. new towns style reflected the opulence a growing bourgeoise and at the same time made this area inaccessible to the working class who were condemned to a life at the bottom of the ladder. While the walls surrounding Edinburgh would eventually be destroyed, the divide between the poor and rich continues, their lives still separated by stone walls.

— JJ